The Steel Wool Project

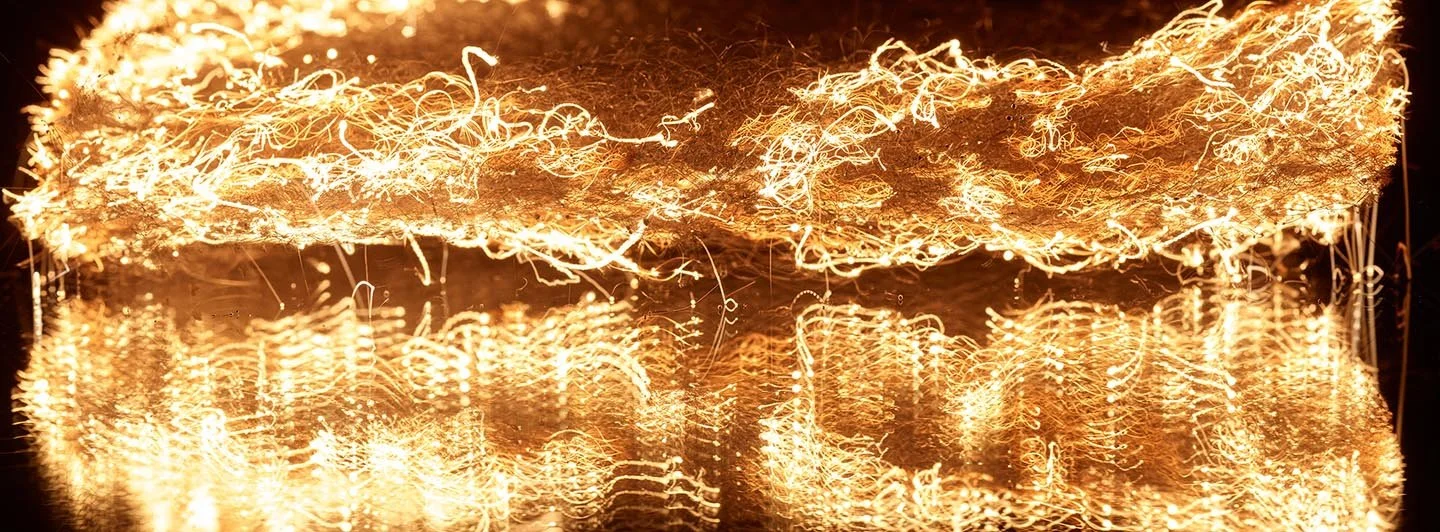

From the Steel Wool Project — Charles Jones, 2025

Introduction

Every now and then, an idea lingers quietly in the background — too undeveloped to act on, yet too persistent to ignore. The Steel Wool Project is one of those ideas. What began as a passing curiosity about light and motion slowly evolved into a study of transformation — from metal to fire, from chaos to order, and from the microscopic to the celestial.

This project became less about documenting a subject and more about exploring what happens when light itself becomes the landscape. Through experiment, patience, and plenty of trial and error, I found not just sparks and embers, but tiny universes suspended in the darkness.

What follows is a short reflection on that process — from the first spark of inspiration to the final stage of bringing the images to life in print.

“This project became less about documenting a subject and more about exploring what happens when light itself becomes the landscape.”

1. Genesis of the Idea

I can’t say exactly where the idea began. Like many creative sparks, it arrived gradually — a slow burn rather than a flash. I’d long admired the luminous, surreal energy of Murray Fredericks’ Flaming Tree series and the controlled, otherworldly glow of Ruben Wu’s artificial light work. Both artists use light not just as illumination, but as an active subject — something to shape, provoke, and redefine the familiar.

At the same time, I’d been looking for something more abstract than my usual landscapes — something that dealt more directly with gesture, texture, and the language of light itself. The concept of burning steel wool lingered in my mind for well over two years. I let it percolate quietly, never quite letting go of the idea but waiting for the right moment — and perhaps the right question — to begin.

2. Research

Before anything could happen, I had to solve two main problems: the technical setup, and the behaviour of the steel wool itself.

First, the camera system. I needed to understand which lenses would allow me to work close enough to the action without compromising field of view or safety. Minimum focusing distance, focal length, and how each lens might render the sparks — these became early points of experimentation on paper before ever striking a match.

Then came the steel wool. What grade would burn most effectively? How long would the ignition last? How many rotations would give a consistent halo of sparks rather than chaos? Even small details like cost and availability came into play — this was not a project I wanted to rush or waste materials on.

3. Execution

After a few trial runs with no camera — just to understand how the wool burned — it was finally time to bring the lens into the equation. This turned out to be much harder than expected. Getting a consistent, repeatable result required a lot of trial and error; I’d estimate at least thirty different attempts before something predictable began to emerge.

Once that consistency arrived, the work shifted from technical exercise to creative expression. At first, I was focused on capturing the movement of light through the fibres — the chaotic spray and miasma of sparks suspended in motion. But as I began studying the cooled remnants, something unexpected appeared: the tiny blobs of burnt residue, illuminated against the darkness, started to resemble distant galaxies — a kind of miniature cosmos born from steel and fire. That discovery changed everything.

4. Refinement

Once I began to recognise those tiny celestial forms within the images — the suggestion of galaxies and the Milky Way scattered through the frame — the project started to take on a new dimension. I found myself experimenting with both scale and perspective: sometimes zooming right in to isolate a single burst of light, other times pulling back to reveal the broader sweep of the composition.

Even during post-production, subtle crops and reframing decisions could shift the work from something grounded and physical to something that felt vast and otherworldly. The interplay between focus, depth, and abstraction became a way of exploring how far I could stretch the illusion — how close I could come to making the microscopic appear cosmic.

It was in these refinements that the work began to feel alive — less about the mechanics of burning steel wool, and more about finding galaxies hidden in the aftermath of fire.

5. Where to from Here

The next stage is the most exciting part for me: printing. After months of experimentation behind the camera, it’s now about bringing these images into the physical world and seeing how they behave on paper.

I plan to explore a range of papers — from satin and gloss to matte and Canson Photo Rag — to understand how each surface interacts with the texture and luminosity of the sparks. Because the steel wool itself is so inherently tactile, I’m curious whether a more textured paper might echo that quality and give the print an extra sense of dimensionality.

This will be a process of discovery as much as creation — testing, comparing, and letting the materials guide the outcome. It feels like a fitting continuation of the project: letting something elemental and unpredictable reveal its form one stage at a time.